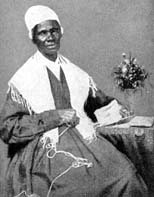

WOMEN IN HISTORY - SOJOURNER TRUTH

African-American abolitionist, Civil War nurse, suffragette

DATE OF BIRTH

Born - Isabella Baumfree - 1797

|

PLACE OF BIRTH

Ulster County, New York

|

DATE OF DEATH

November 26, 1883

|

PLACE OF DEATH

Battle Creek, Michigan

|

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Sojourner Truth was born in 1797 on the Colonel Johannes Hardenbergh estate in Swartekill, in Ulster County, a Dutch settlement in upstate New York. Her given name was Isabella Baumfree (also spelled Bomefree). She was one of 13 children born to Elizabeth and James Baumfree, also slaves on the Hardenbergh plantation. She spoke only Dutch until she was sold from her family around the age of nine. Because of the cruel treatment she suffered at the hands of a later master, she learned to speak English quickly, but had a Dutch accent for the rest of her life.

EDUCATION

Much of her education was gained while living with her grandmother, Mrs. John Quincy, in Mount Wollaston.

ACCOMPLISHMENTS

She was first sold around age 9 when her second master (Charles Hardenbergh) died in 1808. She was sold to John Neely, along with a herd of sheep, for $100. Neely's wife and family only spoke English and beat Isabella fiercely for the frequent miscommunications. She later said that Neely once whipped her with "a bundle of rods, prepared in the embers, and bound together with cords." It was during this time that she began to find refuge in religion -- beginning the habit of praying aloud when scared or hurt. When her father once came to visit, she pleaded with him to help her. Soon after, Martinus Schryver purchased her for $105. He owned a tavern and, although the atmosphere was crude and morally questionable, it was a safer haven for Isabella. But a year and a half later, in 1810, she was sold again to John Dumont of New Paltz, New York. Isabella suffered many hardships at the hands of Mrs. Dumont, whom Isabella later described as cruel and harsh. Although she did not explain the reasons for this treatment in her later biography narrative, historians have surmised that the unspeakable things might have been sexual abuse or harassment (see the biography on Harriet Jacobs, the only former slave to write about such), or simply the daily humiliations that slaves endured.

Sometime around 1815, she fell in love with a fellow slave named Robert, who was owned by a man named Catlin or Catton. Robert's owner forbade the relationship because he did not want his slave having children with a slave he did not own (and therefore would not own the new 'property'). One night Robert visited Isabella, but was followed by his owner and son, who beat him savagely ("bruising and mangling his head and face"), bound him and dragged him away. Robert never returned. Isabella had a daughter shortly thereafter, named Diana. In 1817, forced to submit to the will of her owner Dumont, Isabella married an older slave named Thomas. They had four children: Peter (1822), James (who died young), Elizabeth (1825), and Sophia (1826).

The state of New York began in 1799 to legislate the gradual abolition of slaves, which was to happen July 4, 1827. Dumont had promised Isabella freedom a year before the state emancipation, "if she would do well and be faithful." However, he reneged on his promise, claiming a hand injury had made her less productive. She was infuriated, having understood fairness and duty as a hallmark of the master-slave relationship. She continued working until she felt she had done enough to satisfy her sense of obligation to him -- spinning 100 pounds of wool -- then escaped before dawn with her infant daughter, Sophia. She later said:

"I did not run off, for I thought that wicked, but I walked off, believing that to be all right."

Isabella wandered, not sure where she was going, and prayed for direction. She arrived at the home of Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen (Wagener?). Soon after, Dumont arrived, insisting she come back and threatening to take her baby when she refused. Isaac offered to buy her services for the remainder of the year (until the state's emancipation took effect), which Dumont accepted for $20. Isaac and Maria insisted Isabella not call them "master" and "mistress," but rather by their given names.

Isabella immediately set to work retrieving her young son Peter. He had recently been leased by Dumont to another slaveholder, who then illegally sold Peter to an owner in Alabama. Peter was five years old. First she appealed to the Dumonts, then the other slaveholder, to no avail. A friend directed her to activist Quakers, who helped her make an official complaint in court. After months of legal proceedings, Peter returned to her, scarred and abused.

During her time with the Van Wagenens, Isabella had a life-changing religious experience -- becoming "overwhelmed with the greatness of the Divine presence" and inspired to preach. She began devotedly attending the local Methodist church and, in 1829, left Ulster County with a white evangelical teacher named Miss Gear. She quickly became known as a remarkable preacher whose influence "was miraculous." She soon met Elijah Pierson, a religious reformer who advocated strict adherence to Old Testament laws for salvation. His house was sometimes called the "Kingdom," where he led a small group of followers. Isabella became the group's housekeeper. Elijah treated her as a spiritual equal and encouraged her to preach also. Soon after, Robert Matthias arrived, who apparently took over as the group's leader, with the activities becoming increasingly bizarre. In 1834, Pierson died with only the group's members attending. His family called the coroner and the group disbanded. The Folger family, whose house the group had moved into, accused Robert and Isabella of stealing their money and poisoning Elijah. They were eventually acquitted and Robert traveled west.

Isabella settled in New York City, but she had lost what savings and possessions she had had. She resolved to leave and make her way as a traveling preacher. On June 1, 1843, she changed her name to Sojourner Truth and told friends, "The Spirit calls me [East], and I must go." She wandered in relative obscurity, depending on the kindness of strangers. In 1844, still liking the utopian cooperative ideal, she joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in Massachusetts. This group of 210 members lived on 500 acres of farmland, raising livestock, running grist and saw mills, and operating a silk factory. Unlike the Kingdom, the Association was founded by abolitionists to promote cooperative and productive labor. They were strongly anti-slavery, religiously tolerant, women's rights supporters, and pacifist in principles. While there, she met and worked with abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and David Ruggles. Unfortunately, the community's silk-making was not profitable enough to support itself and it disbanded in 1846 amid debt.

Sojourner went to live with one of the Association's founders, George Benson, who had established a cotton mill. Shortly thereafter, she began dictating her memoirs to Olive Gilbert, another Association member. The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave was published privately by William Lloyd Garrison in 1850. It gave her an income and increased her speaking engagements, where she sold copies of the book. She spoke about anti-slavery and women's rights, often giving personal testimony about her experiences as a slave. That same year, 1850, Benson's cotton mill failed and he left Northampton. Sojourner bought a home there for $300. In 1854, at the Ohio Woman's Rights Covention in Akron, Ohio, she gave her most famous speech -- with the legendary phrase, "Ain't I a Woman?" :

"That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud puddles, or gives me any best place, and ain't I a woman? ... I have plowed, and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me -- and ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man (when I could get it), and bear the lash as well -- and ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen children and seen most all sold off to slavery and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me -- and ain't I woman?"

Sojourner later became involved with the popular Spiritualism religious movement of the time, through a group called the Progressive Friends, an offshoot of the Quakers. The group believed in abolition, women's rights, non-violence, and communicating with spirits. In 1857, she sold her home in Northampton and bought one in Harmonia, Michigan (just west of Battle Creek), to live with this community. In 1858, at a meeting in Silver Lake, Indiana, someone in the audience accused her of being a man (she was very tall, towering around six feet) so she opened her blouse to reveal her breasts.

During the Civil War, she spoke on the Union's behalf, as well as for enlisting black troops for the cause and freeing slaves. Her grandson James Caldwell enlisted in the 54th Regiment, Massachusetts. In 1864, she worked among freed slaves at a government refugee camp on an island in Virginia and was employed by the National Freedman's Relief Association in Washington, D.C. She also met President Abraham Lincoln in October. (A famous painting, and subsequent photographs of it, depict President Lincoln showing Sojourner the 'Lincoln Bible,' given to him by the black people of Baltimore, Maryland.) In 1863, Harriet Beecher Stowe's article "The Libyan Sibyl" appeared in the Atlantic Monthly; a romanticized description of Sojourner. (The previous year, William Story's statue of the same title, inspired by the article, won an award at the London World Exhibition.) After the Civil War ended, she continued working to help the newly freed slaves through the Freedman's Relief Association, then the Freedman's Hospital in Washington. In 1867, she moved from Harmonia to Battle Creek, converting William Merritt's "barn" into a house, for which he gave her the deed four years later.

In 1870, she began campaigning for the federal government to provide former slaves with land in the "new West." She pursued this for seven years, with little success. In 1874, after touring with her grandson Sammy Banks, he fell ill and she developed ulcers on her leg. Sammy died after an operation. She was successfully treated by Dr. Orville Guiteau, veterinarian, and headed off on speaking tours again, but had to return home due to illness once more. She did continue touring as much as she could, still campaigning for free land for former slaves. In 1879, Sojourner was delighted as many freed slaves began migrating west and north on their own, many settling in Kansas. She spent a year there helping refugees and speaking in white and black churches trying to gain support for the "Exodusters" as they tried to build new lives for themselves. This was to be her last mission.

Sojourner made a few appearances around Michigan, speaking about temperance and against capital punishment. In July of 1883, with ulcers on her legs, she sought treatment through Dr. John Harvey Kellogg at his famous Battle Creek Sanitarium. It is said he grafted some of his own skin onto her leg. Sojourner returned home with her daughters Diana and Elizabeth, their husbands and children, and died there on November 26, 1883, at 86 years old. She was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery next to her grandson. In 1890, Frances Titus, who published the third edition of Sojourner's Narrative in 1875 and became Sojourner's traveling companion after Sammy died, collected money and erected a monument on the gravesite, inadvertently inscribing "aged about 105 years." She then commissioned artist Frank Courter to paint the meeting of Sojourner and President Lincoln.

Sojourner Truth has been posthumously honored in many ways over the years:

Sometime around 1815, she fell in love with a fellow slave named Robert, who was owned by a man named Catlin or Catton. Robert's owner forbade the relationship because he did not want his slave having children with a slave he did not own (and therefore would not own the new 'property'). One night Robert visited Isabella, but was followed by his owner and son, who beat him savagely ("bruising and mangling his head and face"), bound him and dragged him away. Robert never returned. Isabella had a daughter shortly thereafter, named Diana. In 1817, forced to submit to the will of her owner Dumont, Isabella married an older slave named Thomas. They had four children: Peter (1822), James (who died young), Elizabeth (1825), and Sophia (1826).

The state of New York began in 1799 to legislate the gradual abolition of slaves, which was to happen July 4, 1827. Dumont had promised Isabella freedom a year before the state emancipation, "if she would do well and be faithful." However, he reneged on his promise, claiming a hand injury had made her less productive. She was infuriated, having understood fairness and duty as a hallmark of the master-slave relationship. She continued working until she felt she had done enough to satisfy her sense of obligation to him -- spinning 100 pounds of wool -- then escaped before dawn with her infant daughter, Sophia. She later said:

"I did not run off, for I thought that wicked, but I walked off, believing that to be all right."

Isabella wandered, not sure where she was going, and prayed for direction. She arrived at the home of Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen (Wagener?). Soon after, Dumont arrived, insisting she come back and threatening to take her baby when she refused. Isaac offered to buy her services for the remainder of the year (until the state's emancipation took effect), which Dumont accepted for $20. Isaac and Maria insisted Isabella not call them "master" and "mistress," but rather by their given names.

Isabella immediately set to work retrieving her young son Peter. He had recently been leased by Dumont to another slaveholder, who then illegally sold Peter to an owner in Alabama. Peter was five years old. First she appealed to the Dumonts, then the other slaveholder, to no avail. A friend directed her to activist Quakers, who helped her make an official complaint in court. After months of legal proceedings, Peter returned to her, scarred and abused.

During her time with the Van Wagenens, Isabella had a life-changing religious experience -- becoming "overwhelmed with the greatness of the Divine presence" and inspired to preach. She began devotedly attending the local Methodist church and, in 1829, left Ulster County with a white evangelical teacher named Miss Gear. She quickly became known as a remarkable preacher whose influence "was miraculous." She soon met Elijah Pierson, a religious reformer who advocated strict adherence to Old Testament laws for salvation. His house was sometimes called the "Kingdom," where he led a small group of followers. Isabella became the group's housekeeper. Elijah treated her as a spiritual equal and encouraged her to preach also. Soon after, Robert Matthias arrived, who apparently took over as the group's leader, with the activities becoming increasingly bizarre. In 1834, Pierson died with only the group's members attending. His family called the coroner and the group disbanded. The Folger family, whose house the group had moved into, accused Robert and Isabella of stealing their money and poisoning Elijah. They were eventually acquitted and Robert traveled west.

Isabella settled in New York City, but she had lost what savings and possessions she had had. She resolved to leave and make her way as a traveling preacher. On June 1, 1843, she changed her name to Sojourner Truth and told friends, "The Spirit calls me [East], and I must go." She wandered in relative obscurity, depending on the kindness of strangers. In 1844, still liking the utopian cooperative ideal, she joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in Massachusetts. This group of 210 members lived on 500 acres of farmland, raising livestock, running grist and saw mills, and operating a silk factory. Unlike the Kingdom, the Association was founded by abolitionists to promote cooperative and productive labor. They were strongly anti-slavery, religiously tolerant, women's rights supporters, and pacifist in principles. While there, she met and worked with abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and David Ruggles. Unfortunately, the community's silk-making was not profitable enough to support itself and it disbanded in 1846 amid debt.

Sojourner went to live with one of the Association's founders, George Benson, who had established a cotton mill. Shortly thereafter, she began dictating her memoirs to Olive Gilbert, another Association member. The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave was published privately by William Lloyd Garrison in 1850. It gave her an income and increased her speaking engagements, where she sold copies of the book. She spoke about anti-slavery and women's rights, often giving personal testimony about her experiences as a slave. That same year, 1850, Benson's cotton mill failed and he left Northampton. Sojourner bought a home there for $300. In 1854, at the Ohio Woman's Rights Covention in Akron, Ohio, she gave her most famous speech -- with the legendary phrase, "Ain't I a Woman?" :

"That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud puddles, or gives me any best place, and ain't I a woman? ... I have plowed, and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me -- and ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man (when I could get it), and bear the lash as well -- and ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen children and seen most all sold off to slavery and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me -- and ain't I woman?"

Sojourner later became involved with the popular Spiritualism religious movement of the time, through a group called the Progressive Friends, an offshoot of the Quakers. The group believed in abolition, women's rights, non-violence, and communicating with spirits. In 1857, she sold her home in Northampton and bought one in Harmonia, Michigan (just west of Battle Creek), to live with this community. In 1858, at a meeting in Silver Lake, Indiana, someone in the audience accused her of being a man (she was very tall, towering around six feet) so she opened her blouse to reveal her breasts.

During the Civil War, she spoke on the Union's behalf, as well as for enlisting black troops for the cause and freeing slaves. Her grandson James Caldwell enlisted in the 54th Regiment, Massachusetts. In 1864, she worked among freed slaves at a government refugee camp on an island in Virginia and was employed by the National Freedman's Relief Association in Washington, D.C. She also met President Abraham Lincoln in October. (A famous painting, and subsequent photographs of it, depict President Lincoln showing Sojourner the 'Lincoln Bible,' given to him by the black people of Baltimore, Maryland.) In 1863, Harriet Beecher Stowe's article "The Libyan Sibyl" appeared in the Atlantic Monthly; a romanticized description of Sojourner. (The previous year, William Story's statue of the same title, inspired by the article, won an award at the London World Exhibition.) After the Civil War ended, she continued working to help the newly freed slaves through the Freedman's Relief Association, then the Freedman's Hospital in Washington. In 1867, she moved from Harmonia to Battle Creek, converting William Merritt's "barn" into a house, for which he gave her the deed four years later.

In 1870, she began campaigning for the federal government to provide former slaves with land in the "new West." She pursued this for seven years, with little success. In 1874, after touring with her grandson Sammy Banks, he fell ill and she developed ulcers on her leg. Sammy died after an operation. She was successfully treated by Dr. Orville Guiteau, veterinarian, and headed off on speaking tours again, but had to return home due to illness once more. She did continue touring as much as she could, still campaigning for free land for former slaves. In 1879, Sojourner was delighted as many freed slaves began migrating west and north on their own, many settling in Kansas. She spent a year there helping refugees and speaking in white and black churches trying to gain support for the "Exodusters" as they tried to build new lives for themselves. This was to be her last mission.

Sojourner made a few appearances around Michigan, speaking about temperance and against capital punishment. In July of 1883, with ulcers on her legs, she sought treatment through Dr. John Harvey Kellogg at his famous Battle Creek Sanitarium. It is said he grafted some of his own skin onto her leg. Sojourner returned home with her daughters Diana and Elizabeth, their husbands and children, and died there on November 26, 1883, at 86 years old. She was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery next to her grandson. In 1890, Frances Titus, who published the third edition of Sojourner's Narrative in 1875 and became Sojourner's traveling companion after Sammy died, collected money and erected a monument on the gravesite, inadvertently inscribing "aged about 105 years." She then commissioned artist Frank Courter to paint the meeting of Sojourner and President Lincoln.

Sojourner Truth has been posthumously honored in many ways over the years:

- a memorial stone in the Stone History Tower in Monument Park, downtown Battle Creek (1935);

- a new grave marker, by the Sojourner Truth Memorial Association (1946);

- a historical marker commemorating members of her family buried with her in the cemetery (1961);

- a portion of Michigan state highway M-66 designated the Sojourner Truth Memorial Highway (1976);

- induction into the national Woman's Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York (1981);

- induction into the Michigan Woman's Hall of Fame in Lansing (1983);

- a commemorative postage stamp (1986);

- a Michigan Milestone Marker by the State Bar of Michigan for her contribution (three lawsuits she won) to the legal system (1987);

- a marker erected by the Battle Creek Club of the National Association of Negro Business and Professional Women's Clubs (also 1987);

- a Mars probe named for her (1997);

- a community-wide, year-long celebration of the 200th anniversary of her birth in Battle Creek in 1997, plus a larger-than-life statue of her by artist Tina Allen; and

- the First Black Woman Honored with a Bust in the U.S. Capitol (October, 2008)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Braude, Ann. Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women's Rights in Nineteenth-Century America. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1989.

- Commire, Anne, editor. Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Waterford, Conn.: Yorkin Publications, 1999-2000.

- Hooks, Bell. Ain't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism. Boston, MA: South End, 1981.

- Johnston, Paul E., and Sean Wilentz. The Kingdom of Matthias. NY: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Mabee, Carleton. Sojourner Truth: Slave, Prophet, Legend. NY: New York University Press, 1993.

- Painter, Nell Irvin. Sojourner Truth: A Life, a Symbol. NY: W.W. Norton, 1996.

- Pauli, Hertha Ernestine. Her Name Was Sojourner Truth. NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1962.

- Slave Narratives. NY: Library of America, 2000.

- Stetson, Erlene, and Linda David. Glorying in Tribulation: The Lifework of Sojourner Truth. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 1994.

- Stewart, James Brewer. Holy Warriors: The Abolitionists and American Slavery. NY: Hill and Wang, 1976.

- Truth, Sojourner. Narrative of Sojourner Truth; a Bondswoman of Olden Time, Emancipated by the New York Legislature in the Early Part of the Present Century with a History of her Labors and Correspondence, Drawn from Her Book of Life. Battle Creek, MI: Published for the Author, 1878. Later printing, with introduction by Margaret Washington: NY: Vintage Books, 1993.

WEBSITES

- Sojourner Truth Institute

- Sojourner Truth - Stamp on Black History profile

- Sojourner Truth - Memorial Statue Project in Florence, Massachusetts

- Sojourner Truth - Battle Creek Historical Society

- "Ain't I a Woman?" Speech - Fordham University

- "Ain't I a Woman?" - speech and history of, on About.com

- "Keeping the Thing Going While Things are Stirring" - speech delivered at the American Equal Rights Association in 1867

- The Narrative of Sojourner Truth - online text of her autobiography, at A Celebration of Women Writers

- Sojourner Truth, the Libyan Sibyl - Article by Harriet Beecher Stowe, appeared in the Atlantic Monthly in April 1863

- Women and Families in Slavery - links to essays and first-hand accounts and letters about the lives of female slaves

- "Sojourner Truth will Become the First Black Woman Honored with a Bust in the U.S. Capitol"

CITATION

This page may be cited as:

Women in History. Sojourner Truth biography. Last Updated: 2/27/2013. Women In History Ohio.

<http://www.womeninhistoryohio.com/sojourner-truth.html>

Women in History. Sojourner Truth biography. Last Updated: 2/27/2013. Women In History Ohio.

<http://www.womeninhistoryohio.com/sojourner-truth.html>